Jafar (pseudonym), a 15-year-old Rohingya child, currently lives in the Rohingya camp in Ukhiya. He used to live peacefully with his parents until one day, some people forcibly took him into a car. He had no idea what was happening. After a while, he realized he had been abducted. When Jafar tried to shout, they tried to calm him down by saying he was being taken outside the camp to work so that he could support his family financially. Risking his life, he jumped out of the car and hid in a jungle. A nearby shopkeeper saw him and called an NGO official to rescue him. With the help of that NGO, he reached his home. He said he would never forget this horrific experience.

The alarming rise in trafficking of Rohingya children poses a significant challenge, driven by multiple contributing factors. In just the first quarter of 2024, the Joint Protection Monitoring Report recorded 79 cases of human trafficking involving refugees within Bangladesh, with 13 children identified as victims. Extreme poverty, lack of livelihood opportunities, and the vulnerability of displaced families create fertile ground for traffickers to exploit children. Many traffickers lure children and their families with false promises of work, while these children are abducted for forced labor, sexual exploitation, or even coerced into illegal activities such as drug trafficking.

In Jafar’s case, there are two possibilities: either he was kidnapped for ransom, or he was kidnapped for child trafficking. Regardless of the situation, after Jafar’s rescue, his family faces some serious questions. What is their legal status in Bangladesh? Are their children entitled to the same rights as Bangladeshi children? How can they navigate the Bangladeshi legal system to protect their child?

Recently, I had the opportunity to seek answers to these questions through a study assessing the needs and challenges faced by Rohingya children in accessing justice. As part of the Innovision team, I conducted this study to evaluate the accessibility, efficiency, and effectiveness of existing justice mechanisms and services for children in the Rohingya camps.

National and international laws and policies are fundamental to understanding the context of the justice mechanism for Rohingya children. Each question concerning Jafar’s family necessitates a comprehensive review of relevant legal and policy frameworks. For instance, regarding Jafar’s status in Bangladesh, it is important to note that he is classified not as a refugee but as a Forcibly Displaced Myanmar National (FDMN) under Bangladeshi law. Since Bangladesh has not signed or ratified the 1951 Refugee Convention, individuals in Jafar’s position cannot be legally described as refugees. However, in 2017, the Supreme Court of Bangladesh ruled that the 1951 Refugee Convention had “evolved into customary international law, which is obligatory for all nations worldwide, regardless of whether a specific country has formally agreed to or ratified the Convention.”

In addressing the second question that arose in the minds of Jafar’s parents, the Children Act of Bangladesh does not make any distinction between Bangladeshi children and Rohingya children. This legal framework was enacted to implement the provisions of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) and applies equally to all children within the jurisdiction of Bangladesh, regardless of their status. Hence, Rohingya children are entitled to the same rights as Bangladeshi children.

However, it was found that most of the child respondents in the Rohingya camps, who were either in conflict with the law, in contact with the law, or classified as disadvantaged children, had never been to a children’s court. These children and their families heavily relied on the informal justice system. In the Rohingya camps, the key actors in the informal justice system are the majhis, who generally serve as the primary mediators when conflicts arise. Although majhis are not mandated to resolve disputes, camp authorities grant them the authority to mediate.

This informal justice system is not without its drawbacks. There are allegations of corruption and dishonesty against some majhis. Additionally, some majhis are intimidated by armed groups, leading them to make partial and unfair decisions. The entire informal system lacks legal authority and perpetuates harmful gender power dynamics, undermining girls’ rights.

On the other hand, key informant interviews with Government officials revealed that the courts typically take every case, regardless of whether it involves Rohingya or Bangladeshi individuals. Nevertheless, they encourage resolving disputes within the camps, as the existing court system is already overburdened with cases from the host community.

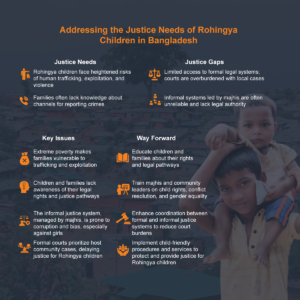

Navigating the justice system for Rohingya people is complex and confusing. We found that, like Jafar, more than half of the total surveyed population did not know where or to whom they should report an offence. This knowledge gap further exacerbates the existing challenges in accessing the formal justice system. Therefore, policymakers must take action to ensure an effective and responsive justice framework in the camps, in line with the Children Act of 2013, the UNCRC, and other international standards.

In this context, it is crucial to raise awareness about children’s rights and the support services available for reporting crimes and injustices. Key stakeholders must strengthen the capacity of community leaders through training on conflict resolution, mediation techniques, child rights, and gender equality. In addition to training, clear guidelines and codes of conduct for informal justice mechanisms are necessary. Furthermore, creating a platform for sharing information and best practices between formal and informal justice actors can enhance the overall effectiveness of the justice system for Rohingya children.

There is an urgent need for a comprehensive and multi-faceted approach to address the justice needs of Rohingya children in Bangladeshi refugee camps. The challenges faced by Rohingya children are complex and interconnected, requiring interventions at the individual, community, and systemic levels. By prioritizing legal awareness, psychosocial support, and access to child-friendly justice mechanisms, we can empower Rohingya children to seek and obtain the justice they deserve. This will not only protect their rights but also contribute to their overall well-being and resilience in the face of adversity.

Author: Sadia Siddique Katha a Junior Associate in the Gender and Basic Services Portfolio at Innovision Consulting