Bangladesh, responsible for only 0.56% of global greenhouse gas emissions, stands among the countries most vulnerable to the climate crisis. Its low-lying landscape, dense population, and reliance on agriculture expose millions to the severe consequences of rising sea levels, floods, and cyclones. While wealthier citizens can access resources to mitigate these risks, the country’s poor—especially those in southern coastal areas, smallholder farmers, and urban migrants—bear the brunt of climate impacts.

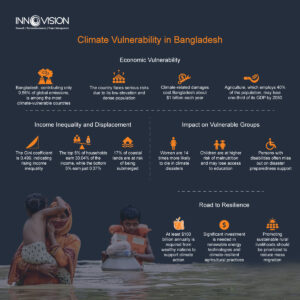

Data from the latest Household Income and Expenditure Survey (HIES) reveals a troubling rise in income inequality. The Gini coefficient reached 0.499 in 2022, up from 0.458 in 2010, indicating that wealth is increasingly concentrated in the hands of a few. The top 5% of households hold around 30.04% of total income, while the bottom 5% hold just 0.37%. This growing disparity exacerbates social and economic inequalities, making it even harder for low-income groups to access essential resources and opportunities to improve their lives.

Climate change is already transforming Bangladesh’s rural and coastal landscapes. According to the WHO, over 7.1 million Bangladeshis were displaced by climate-related events in 2022, a number projected to rise to 13.3 million by 2050. Rising sea levels are expected to submerge around 17% of the country’s coastal land, potentially displacing up to 20 million people by mid-century. This internal migration puts immense strain on urban areas like Dhaka, where displaced individuals often settle in informal settlements with limited access to basic services.

The economic toll is particularly profound in agriculture, a sector that employs about 40% of the population. Without significant global efforts to reduce emissions, projections indicate that Bangladesh could lose up to one-third of its agricultural GDP by 2050 due to climate variability and extreme weather, according to the World Bank. Already, climate variability costs Bangladesh approximately $1 billion annually in disaster damages and lost productivity. Rising salinity, erratic weather, and extreme heat further erode farmers’ livelihoods, threatening both food security and economic stability.

Climate change also affects human capital, particularly in education and healthcare. Displaced children often drop out of school due to financial strain, while wealthier families can afford private education. The urban poor and rural populations face higher risks from waterborne diseases and malnutrition, further widening the healthcare gap.

Women, children, and people with disabilities are especially vulnerable to climate impacts. A UNDP study found that women are 14 times more likely than men to die in climate-induced disasters. The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated these challenges, with a study conducted by Innovision in collaboration with UN Women revealing a 54% drop in monthly income for marginalized women’s families during lockdowns. This economic instability has also fueled gender-based violence, with 73.4% of such incidents linked to poverty, according to the International Rescue Committee. Children are similarly affected, facing increased risks of malnutrition and disrupted education. Persons with disabilities, who make up 2.8% of the population, are often excluded from disaster preparedness efforts due to the lack of accessible facilities.

Addressing Bangladesh’s climate vulnerabilities demands urgent international intervention alongside robust local initiatives. Between 2000 and 2019, the country experienced 185 extreme weather events, incurring over $3.72 billion in annual costs, as reported by the International Centre for Climate Change and Development (ICCCAD). Wealthier nations, historically responsible for much of the world’s emissions, have a moral obligation to assist vulnerable countries like Bangladesh. Commitments such as the Loss and Damage Fund, established at COP27 to compensate developing nations for climate-related destruction, must be honoured. According to international agreements and ongoing discussions within climate negotiations, wealthy nations are required to commit at least $100 billion annually to global climate finance to support adaptation efforts in countries like Bangladesh.

In addition to international support, Bangladesh must enhance its own resilience through local strategies. This includes investing in renewable energy technologies and climate-resilient agricultural practices, such as developing salt-tolerant rice varieties and implementing solar irrigation projects. These initiatives can significantly bolster the resilience of farmers in coastal and drought-prone regions. Moreover, comprehensive migration strategies are essential to address climate-induced displacement within the country. Proactive measures should prioritize the development and promotion of sustainable, climate-resilient rural livelihoods to reduce mass migration. By enhancing agricultural practices and diversifying income sources, communities can better withstand climate shocks and maintain economic stability.

Without decisive global cooperation to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and finance adaptation, countries like Bangladesh will continue to bear an unjust and disproportionate share of the climate crisis. The consequences of inaction will jeopardize millions of lives, livelihoods, and communities, deepening the already stark divide between those who can adapt and those who remain vulnerable. Urgent, tangible action is no longer a matter of choice but a moral responsibility. Wealthy nations, whose emissions have largely fuelled this crisis, must step up to bridge this growing climate divide by honoring financial commitments, supporting sustainable technologies, and ensuring that vulnerable countries have the resources needed to build climate resilience.

Authors: Md Al Imran Rumon is the Head of Business Development and Communications at Innovision, and Mohibbullah Al Maruf is an Associate at Innovision