In February 2025, Bangla Academy removed the sanitary napkin stall from the Ekushey Boi Mela in Bangladesh to honor religious sentiments. While the controversy has settled, it raises an important question—why can’t menstrual hygiene products be seen as normal everyday items in Bangladesh? This is society’s perspective, but women also hide menstruation from society, viewing it as something shameful. Menstrual hygiene management (MHM) is a critical but often neglected aspect of women’s health and well-being.

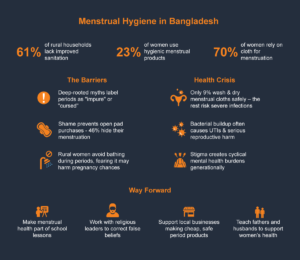

Bangladesh faces challenges in managing menstrual hygiene due to limited access to sanitation facilities and deep-rooted social taboos. According to the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (2018), 61% of rural households and 27% of urban households lack improved sanitation facilities, making it difficult for people to manage menstruation hygienically. Research by Ahmed et al. (2021) highlights that barriers to MHM among Bangladeshi women hinder progress toward achieving Sustainable Development Goals related to health, education, gender equality, and clean water.

Currently, there are five types of menstrual materials commonly used in Bangladesh: cloth, sanitary pads, reusable sanitary pads, menstrual cups, and tampons. However, the World Bank (2022) reports that only 23% of Bangladeshi women use hygienic menstrual materials, such as sanitary pads or other safe alternatives. Many women still rely on unhygienic methods due to economic constraints, limited accessibility, and restrictive social norms.

Cultural restrictions, myths, and psychosocial constructs significantly shape societal attitudes toward menstruation. Many communities perceive menstruation as a divine curse, disease, sin, or punishment rather than a natural biological process. Mohamed et al. (2018) found that some believe menstrual blood is dirty, toxic, or impure, and its sight can bring infertility, blindness, or bad luck to men. As a result, many women prefer to keep menstruation private, often avoiding purchasing sanitary pads openly or discussing their menstrual needs. Instead, they opt for using old, unhygienic cloth to avoid stigma.

Various studies indicate that 70% of Bangladeshi women use cloth to manage their menstruation, while 46% report using sanitary pads regularly (Castro, 2021). However, many women reuse cloth without proper cleaning and drying, leading to potential health risks. Czura (2021) notes that only 9% of women follow the recommended cleaning and drying process for reusable menstrual cloths. Reusing improperly cleaned cloth can lead to bacterial and fungal infections, which can have long-term health consequences.

A recent study by Innovision, in collaboration with WaterAid, examined the accessibility, affordability, and acceptability of menstrual hygiene products in Bangladesh. The study found that society imposes various restrictions on menstruating women, including prohibiting them from praying, entering places of worship, or even visiting markets. Many women also bury used menstrual cloths due to the lack of proper disposal facilities. In rural areas, some women avoid bathing during menstruation due to the belief that it increases blood flow or affects future pregnancies.

The study also revealed that social norms impact the adoption of reusable menstrual products, such as menstrual cups. Many women are unaware of these alternatives, and those who do know about them often hesitate due to cultural fears. Some believe menstrual cups may lead to the loss of virginity or could get stuck inside the body, preventing their widespread use.

Menstruation is a natural biological process, yet misinformation and unhygienic practices have transformed it into a subject of shame. To improve sustainability and public health, it is crucial to challenge these social norms and provide accurate information about menstruation to both women and men.

Innovision proposes several recommendations to address these issues:

- Updating the education curriculum : Schools should include age-appropriate lessons on puberty, menstrual health, and hygiene practices to normalize menstruation and promote proper hygiene. Educating children can also help shift the perspectives of older generations.

- Community awareness programs: Organizing community events can help debunk myths and promote evidence-based menstrual health practices.

- Expanding access to alternative menstrual products: Reusable pads and menstrual cups should be made more accessible, affordable, and widely available. Currently, the lack of local manufacturing and limited availability in pharmacies restricts access.

- Engaging men in awareness efforts: Male school teachers, youth, and elderly men should be involved in discussions to foster a supportive environment for women and girls.

To encourage more women to adopt hygienic menstrual products, affordability and accessibility must be improved. Without these changes, many women will continue following traditional social norms while avoiding safe menstrual practices. The government, NGOs, and private sector should work together to address these challenges.

While shifting societal perceptions is not easy, it is essential for social welfare. Open discussions can help normalize menstruation and eliminate stigma. A collective effort involving education, awareness, and policy support can transform menstruation into a stigma-free process, promoting better health, dignity, and equality for women.

Sources

- Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. (2018). Sanitation and Hygiene in Bangladesh.

- Ahmed, S., et al. (2021). Barriers to Menstrual Hygiene Management in Bangladesh. Journal of Public Health.

- World Bank. (2021). Menstrual Health and Hygiene in South Asia.

- Mohamed, A., et al. (2018). Cultural Myths and Menstrual Health: A Global Perspective.

- Castro, L. (2021). Menstrual Hygiene Practices in Bangladesh: Trends and Challenges.

- Czura, K. (2021). Reusable Menstrual Products: Adoption and Barriers.

Author: Sanchita Sutradhar, Intern in the Gender and Basic Services Portfolio at Innovision Consulting